ARCHITECTURAL REVIEW

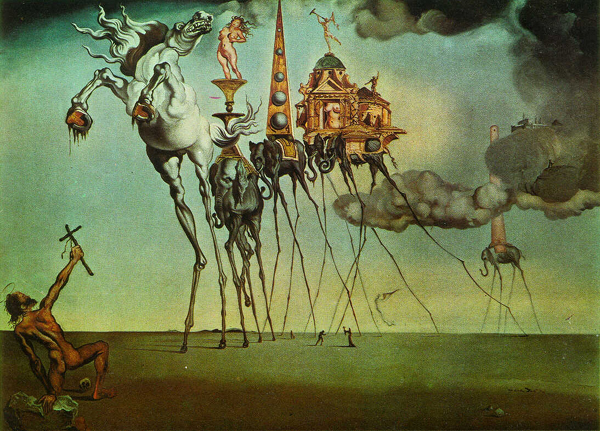

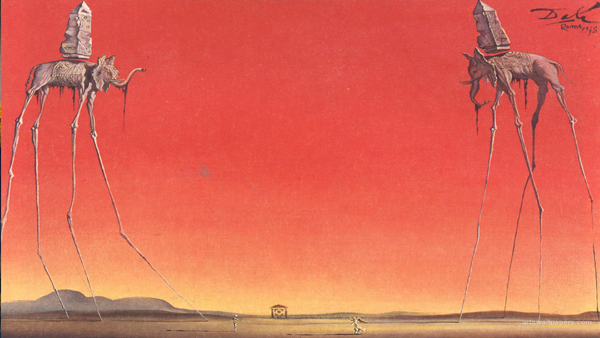

Salvador Dalí, the Temptation of St. Anthony, 1946. The painting is added to a series of the artist's depictions of elephants and other animals carrying architectural compositions while their legs are infinitely stretched, alluding to insects and generating an impression of elevation, of hovering rather than supporting, raising issues relevant to the emergence of architectural pilotis.

We now stand a century past Le Corbusier's launching of the infamous drawing for Maison Dom-ino, a much discussed, provocative parti for standardized reinforced concrete construction in a two-storied free-standing yet expandable iteration. Today, and in the wake of a forthcoming Venice Biennale with its theme calling for a vigorous re-examination of modernism' legacy, the Dom-ino prototype demands rigorous re-assessment as well. In this line of thought, yet only at a nascent stage, and while testing notions that spring from such an analysis of the Dom-ino system and of the pilotis archetype, Aristotheke Eutectonics shall unveil a series of five projects, concerning three villas and two pavilions featuring the _Choe principle.

Expelled Climax

Let us move into the specifics: The Dom-ino prototype emphasizes the presence of the column grid and decidedly moves the means of vertical movement to the exterior of the main rectangular structural bays. Indeed, in the celebrated hand-drawn perspective, the stair is pushed to the far end, its boundaries appearing thus somehow blurred, remaining in the shadow. The landings are almost hidden or visually masked as to screen away the mere fact that the stairwell remains an add-on element, with no further evidence that this prosthetic feat represents an intention - on the contrary, it remains there potentially interfering with the linear continuity of prime spaces.

Surprisingly, the far-end façade fronting the staircase differs geometrically from all other elevations, and particularly to the symmetrically opposite (foreground) short elevation, as clearly depicted in the perspective drawing, while strange visual illusions become prominent here. At first, the landing appears as clearly projecting out of the slab-edge in the long (back) elevation. This composes (for the far-right short side) a list of seemingly unreasonable misalignments to the austerely defined rectangular outlines. In the finished building, the staircase should potentially constitute an entirely different volume, visually and functionally separated from habitable spaces, and would most likely remain an outdoor circulation option.

Cantilevering off a Column

The two-flight stair (per floor) hangs off the main structural plate quite puzzlingly: the stair is slid eccentrically to its adjacent column axis, the remnants (segments) being unequal, greater in front of the two flights, and totally eliminated in the back corner. Structurally, on each floor, the stair lands on a cantilevering rectangle that clearly evades alignment with the front or back ends of the main slabs. From this ultra-small prosthetic cantilever, the actual flights of stairs cantilever once more, and where those meet, at half-floor height, another third-tier cantilever extends, the mid-level landing. It gets frightening particularly when encountering a landing anchored solely on the corner column at mid-height, rather awkwardly - and actually almost wrongly, considering that the stair-edge seems strangely attached to the column, apparently almost containing it rather than simply touching it, altogether aligning to the inner face of its square section. The scaringly weak vertical member, clearly thinner than the floor-slab as mentioned earlier, would be overwhelmed structurally by the asymmetrical and rather disproportionate loads of the two-tiered stair and the bearing of a cantilevered landing connecting those, let alone the horizontal loads pushing the column at mid-height through the concrete diagonal plates of the diagonal flights. Seismically speaking, the column would be suspect of breaking in half because of the stair loads, thus leading the entire bay to a full collapse.

The concept of _Choe as relating to the archetype of pilotis: Phased analysis. (Phot. Editing Maria Roussaki).

However we may assume that the - structurally - clearly unresolved scheme for the stair might have been purposefully understated or neglected as to offer visual preeminence on the clear square shapes of the main structural bays. Alternatively, we may assume that the Dom-ino prototype is a serial and not a self-supporting pod, thus the stair would receive support from another row of columns in its free-standing face - even if the structural scheme would still be very rough. In any case, the failure or denial to combine the absoluteness of the square grid to the functional demands for stairs, elevators, service shafts and other vertical passages of utilitarian scope, precisely pushes the scheme out of the "five points of architecture" announced by the Dom-ino's very author: the columns win the battle of specular geometry and suddenly nothing else fits in.

Erected solely on Pillars

Perhaps willing to avoid associations with previous historical references such as timber-frame structures, in the Dom-ino perspective LC renders concrete slabs as inseparable, meaning not divided between beams and plates, but as an entirely monocoque elements resting on columns. We do not confront thus a post-and-beam parti, a skeletal framework, but decks, thickened surfaces pierced by stilts. Horizontal members - alluding to sandwiched slabs containing hollow chambers, i.e. a covered waffle slab - are evidently drawn much thicker than vertical ones. This represents an insistence on a 'point system' as the sole device of vertical support, as to emphasize the negation of walls and linear elements for that purpose: to withstand gravity, modern architecture assumingly needed no more walls; it just took a grid of needle-thin vertical axes. And this indeed has been a major breakthrough for such 'next-generation' architectures, the perceptual rejection of closed-figure linearly-extruded elements as the primary components of architectural design. Architects would no more need to animate boring boxes; volume was no more the defining monad of design, it had all exploded into vectors and surfaces - not bad.

Offsetting Alignments

In decomposing the boxy conventions of tectonics, edge-to-edge wall connections had to be challenged and ideally undone as well. Truly, columns are pushed off the periphery, and walls have been sliced or torn-off. At the short side of the concrete slabs, a minimal setback of the column axes from the edge is effectively just right to allow a non-bearing perimeter enclosure wall run in-between uninterrupted, rendering thus columns as simply attached to such a partition. In the long (frontal) elevations, the slab overhang is greater, appropriate to let columns stand free when the total floor area is enclosed by a perimeter wall, or alternatively, this very projection is deep enough to provide for a balcony cantilevering out from an enclosed volume that sits back touching the columns as in the short frontages. Indeed, the differing relation of column to perimeter is a strong statement materialized in the Villa Savoye. Simultaneously to such architectural maneuvers, the very sectional profile of the double cantilever remains an optimal structural scheme.

Doric Pilotis

In the Parthenon, columns formulate solely a perimeter stoa and constitute an entirely secondary structural system animating the periphery, while a rigid stone-masonry box is the central core system of earthquake resistance. And this stands closer to the truth: that column-only designs are a naiveté and that, otherwise, columns require braces and stiffeners, shear walls and linear or three-dimensional structural elements to withstand the elements; high winds, typhoons, seismic activity. Programmatically though, the Villa Savoye also negates pilotis, only as much as a Greek temple does: in the notorious villa, pilotis are only symbolically 'open.' While a large segment of uses remains on-ground, the percentage of floor area devoted to enclosed functional entities, as much as to unavoidable elements, i.e. stairs etc. is great, and therefore the pilotis' void space seems more pertinent to a stoa, in any case; to a thin linear and covered space developed between a colonnade and a masonry wall. The sole difference with a classical temple is the visual recess of the vertical piles; a mere shadow-line. Yet the typology of a stoa that turns around to itself, defines a closed perimeter seemingly endless in length, is an absolutely classical choice; and this is essentially pilotis.

A Podium that negates its Presence

Another notable feature of the same LC drawing is the existence of carefully outlined and hatched shadows on concrete foundations that seem emphatically detached from their resting plane, rendered as elements that would remain unburied and visible, or at least such appears to be the intention architecturally. Foundations are thus here another species of pilotis, a second layer, a duplicate datum raising the entire cubical (implied) volume up. This exactly replicates the notion of lifting a building on a sheaf of supports; or a fascio of pillars, alluding to the Casa del Fascio in a strange way. The distortion of extended supports or legs is not uncommon in the period of modernism's growth: Dalí's elephant caravan with the mammals' over-extended, super-stretched legs may be seen as the ultimate dazzling case of this 'elevating' notion.

Salvador Dalí, Elephants, 1948.

Conceptually Faking Pilotis

Lifted up on piers, the Dom-ino scheme becomes a Pilotage (construction en pilotis) and simultaneously a reference to the acclaimed high technology of airspace industries, re-introducing the house-as-cockpit, a flying abode detached from the ground and now floating, or even held-down like a zeppelin rather than pushed-up by stilts. Architecture is thus raised on a pedestal, establishing an artificial plateau detached from the earth crust and overseeing the natural; sitting on it similarly to an airspace shuttle that has just landed, simulating the virtually kinetic.

In the Ville Radieuse we read that primary intention of pilotis was the undisturbed continuation of the natural landscape under man-made structures. The column grid was merely a necessity - structural - architecturalized; organized into a formal system. Yet buildings inevitably have to bridge with the ground through passageways of enclosed space - their entry at least - often growing conceptually into a lobby, the entrance hall, accommodating obvious means of vertical movement; stairs and elevators. This fact, along with the practical aspects of circulation for people, services and goods, remains in constant tension with the fundamental premise of pilotis in negating all contact to the ground.

Pouring down from a Zeppelin

The 2014 _Choe series by Aristotheke Eutectonics specifically addresses the nascent outset of pilotis by lifting all indoor spaces and enclosed volumes off-ground and removing all normative columns as well, while replacing those by the structurally-geared volumes of stairs and elevators or shafts reaching down to the ground from the main floor. These three-dimensional (inescapable) elements are the sole means linking the remote living plateaus to the natural terrain. This constitutes a re-reading of the Dom-ino scheme, emphasizing programmatic priorities rather than an abstraction of structural minimalism as the original 1914 scheme.

In Classical Hellenic ceramics an amphora is a larger container for various liquids, yet used primarily for transport and storage. On the table, the smaller ceramic jar, or rather, a pitcher, designed to sit on a flat surface and avoid dripping while pouring, is the Chous series. Pouring is the act that defines morphologically the 2014 interpretation of the Dom-ino. Key difference (among others) between a single-handle oenochoe (or olpe, wine jug of ancient Greece) from a hydria (three-handle water pot for transportation as well as serving) is the characteristic distortion at the top lip of the vessel, an open spout, an outward beaking for the pouring of wine, mostly generating a trefoil outline in plan. Equally to this customization of the otherwise symmetrical and revolving solids of the vases, the _Choe projects lose their absoluteness and symmetry as to generate routes, their legs, for the flow of people and matter between man-made (up) and natural (down) plateaus, presenting various interpretations of the central outset.

Limping Architecture or architecture on a Limb

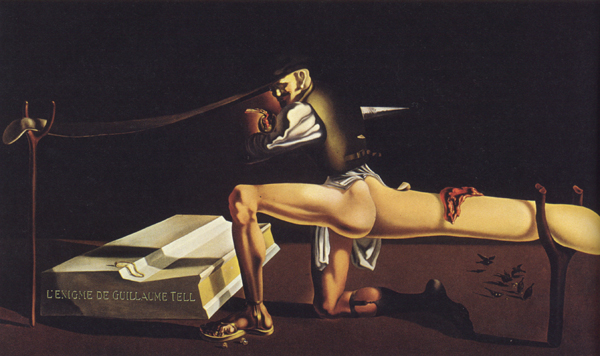

Pilotis automatically depict another notion binary to flotation and oscillation, or actually, contradictory to it: the witnessing of an inability to hold one's position otherwise; to withstand gravity. This is a reverse iteration of the positive uplift as discussed in the above text. Simultaneously to all notions of the sublime, architecture on pilotis is limping, depends on appendages that fetishize it in diverse ways. The _Choe series instead of undoing this liquidity by way of crutches, celebrates the notions of fluidity and lingering, of softness and limbo that otherwise raise a demand for prosthetic support; The _Choe series specifically channels this vaccilation and fluctuation. Monocoque architecture is cast and frozen into place as melting into the ground through human-scale spouts that become at once passages, formal and structural systems in their own right. Instead of entire elephants, we know keep solely their trunks, the proboscis.

Salvador Dalí, The Enigma of William Tell, 1933, Last painting of a trilogy: The principle of wooden crutches.

Sample photograph of ancient Greek Oenochoe with open spout.

by Aristotelis Dimitrakopoulos, Director, Aristotheke Eutectonics

Related articles:

- Escalteca of the Choetheque Series ( 01 April, 2014 )

- Schottheke of the Choetheque Series ( 01 June, 2014 )

- Floatheca Rh of the Choetheque Series ( 01 August, 2014 )

- Floatheca Sp of the Choetheque Series ( 26 September, 2014 )

- O-theke of the Choetheque Series ( 11 March, 2015 )

- Floatheca Cy of the Choetheque Series ( 03 January, 2015 )

- Ophthalteca ( 24 June, 2015 )

- Y-theca of the Choetheque Series ( 08 October, 2015 )