COLUMNS

360º Architecture

As expected, despite irrefutable scientific evidence for climate change and pending catastrophe, the unprecedented mobilization of people in every country, sculptures of emaciated humans standing outside the talks venue, and mounting diplomatic pressure, the UN Climate Change Conference in Copenhagen (7-18 December) produced wide-spread disappointment, especially among the most vulnerable developing countries, and no meaningful agreement or binding commitments to substantial cuts of greenhouse gas emissions, at least not any near the levels recommended by the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and what the planet needs. 'Whatever happens in Copenhagen', Kenyan environmental and political activist Wangari Maathai said few days before the summit, 'go out and plant a tree'.(1) Nobel Peace Prize-winner Maathai believes that fighting for a clean environment is a way to fight against violations of human rights. And as many scientists, architects, artists and inventive communities have shown, if you are concerned about the planet, you can also go out and design with available resources, cheap, ad-hoc materials and discarded waste, unlocking their poetic potential, while generating 0 gas emissions.

At a three-day symposium at St James's Palace in London, last May, where some 60 scientific experts and 20 Nobel Laureates gathered to talk about climate change, Professor Steven Chu, the Nobel Prize-winning US Energy Secretary, suggested that, if we paint the roofs and pavements of our cities a light colour, we would achieve a reduction of carbon emissions equivalent to taking all cars off the roads for 11 years. These surfaces would reflect solar radiation, preventing heat from being absorbed by dark surfaces, where it is trapped by greenhouse gases and increases temperatures. It is simple, cheap and low-tech, and this benign solution has already influenced regulation: since 2005, California has required all flat roofs on commercial buildings to be white. Art Rosenfeld, a member of the California Energy Commission, with his colleagues Hashem Akbari and Surabi Menon, have calculated that changing surface colours in 100 of the world's largest cities could save the equivalent of 44 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide, equivalent to the expected rise of global carbon emissions over the next decade.

Although public support for wind power in the UK appears consistently strong in opinion polls, according to the British Wind Energy Association, in the last two years the number of large windfarm projects gaining approval from local councils in England has slumped from 57% to and all-time low of just 25%. Despite the UK's enormous wind, wave and tidal-power potential (this windswept island has the best potential for wind-power generation in Europe), the UK ranks near the bottom of the EU league table for development of renewable energy.(2) Campaigners against wind farms claim that they pose a threat to landscapes of outstanding natural beauty and disturb walkers' views. It seems that the idea of turning the rare image of a snow-covered Paris or Rome into a permanent one is considered so inconceivable that, regardless of the obvious benefits and the urgency of the situation, not many Europeans appear to have taken Steven Chu's simple and effective proposal any seriously, even though global financial uncertainties are likely to have considerable disruptive effects on the development of complex high-tech solutions, and 'the idea that a massive nuclear program can be developed rapidly and safely is highly questionable'.(3)

Last month, India's environment minister Jairam Ramesh insisted that giving up beef can drastically reduce greenhouse emissions and slow down global warming. In fact, the benefit to the environment would be greater than giving up on cars. According to a report by the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO), livestock is a major threat to the environment, generating 18% of gas emissions, that is, more than transport.(4) Measures to curb and control greenhouse gases and combat global warming will have to be both high and low-tech, both government and grassroot-led. But easy, cheap and low-tech proposals seem to face a kind of resistance that seems absurd, all the more so for being fought on aesthetic fronts. Anyway, are wind turbines so unappealing because they are objectively ugly or because they do not conform to our current perceptions of beauty? In the particular case of the UK, popular resistance to the rationalist and functionalist beauty of wind turbines is undoubtedly related to the historical British denigration of Modernist aesthetics. The conservative preservation of a particular kind of aesthetic appreciation of nature is valued over the survival of nature, and with it over the right of future generations to opt for a new aesthetics of nature. Yet, unprejudiced children have been charmed by a creature as awkward as Pixar Animation Studios' WALL·E ('Waste Allocation Load Lifter - Earth Class'), and rural and urban communities around the world, where material scarcity is a fact of life and improvisation a matter of survival, have used imagination, craft and scrap to creatively reinvent, recycle, re-purpose and ingeniously transform one generation's junk to another's jewels.

Traditionally, Christmas trees in Germany are decorated with straw stars. Today's ecologically-minded Germans have discovered the beauty of colourful stars made of discarded tins. Scarcity of materials has often given rise to the most imaginative projects in art, architecture, decoration, fashion, cuisine, music and every other area of human endeavour. Vintage, pre-embargo American cars are endlessly reconditioned in Cuba, without access to parts from the US, and mainly used as tourist taxis. In Brazil and Africa, amazing jewellery is made of seeds and sea shells; in so many places, toys and all kinds of decorations are made of discarded cans and plastic waste. For last New Year's celebrations, the residents of the Getsemani neighbourhood of Cartagena de Indias, in Colombia, held their street-party under a lightweight, playful canopy, composed of thousands of blue and white plastic bags, functional, beautiful and festive.

Christmas-tree decorations, Germany, 2009, photograph by Styliane Philippou

Havana, Cuba, 2009, photographs by Styliane Philippou

Jewellery from Brazil and Mali, 2009, photograph by Styliane Philippou

Mali, 2005, photograph by Styliane Philippou

Getsemani, Cartagena de Indias, Colombia, 1 January 2009, photographs by Styliane Philippou

Jugaad, a striking shimmering pavilion of 70 square metres, designed by artist Sanjeev Shankar, was first exhibited at the 48°C Public.Art.Ecology festival, held in New Delhi in December 2008. It was constructed in a period of three months with the help of Rajokri villagers out of 692 discarded oil cans. 'The project takes its name from a hindi term which refers to attaining any object with the available resources at hand. By combining this attitude with an open-source, inclusive process,' Shankar explains, 'the project took recycling and reuse beyond a simple utilitarian measure into an exciting adventure of defiance and collective will'. At first, there was a lot of resistance from the villagers, says Shankar, both to the idea of working with an outsider and to that of exploring 'a common symbol of "waste"'.(5) But the temporary pavilion rose like a magic carpet, hung confidently like a spectacular hammock, and convinced all.

Since 1993, Auburn University architecture students at the Rural Studio (established by architecture professors Dennis K. Ruth and the late Samuel Mockbee), in Hale County, West Alabama, have designed and built a long list of houses and civic projects, vastly improving living conditions in one of the poorest counties in the US. Especially during the first years of its existence, the Rural Studio relentlessly explored alternative materials such as paper, textile and garment waste, and the recycling of used building materials, cast-off wood, tin, car windshields and number plates, and other unusual resources.

The extraordinary originality and densely exploratory nature of the Escuela Nacional de Arte (ENA), in Havana (by Ricardo Porro, Roberto Gottardi and Vittorio Garatti, 1961-65, incomplete), is owed to a large extent to the fact that, following the imposition of the US economic blockade on 19 October 1960, Cuba had no access to imported materials such as steel and cement, which led the architects to choose brick and terracotta tiles as the primary materials for the construction of the schools. With the help of Spanish master masons Gumersindo and José Bacallao, the bóveda catalana, the Catalan vault, became the primary structural system used for the architectural complex that epitomises the utopian aspirations of the Cuban Revolution in the 1960s.(6)

Ricardo Porro, School of Plastic Arts, 1961-65, Escuela Nacional de Arte (ENA), Havana, Cuba,

photograph by Styliane Philippou

Vittorio Garatti, School of Music, 1961-65, Escuela Nacional de Arte (ENA), Havana, Cuba,

photograph by Styliane Philippou

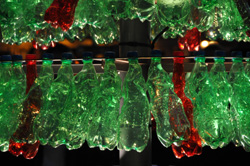

Admittedly, despite appearances, not all objects that use recycling or what appears like junk are innocent, let alone ethically minded. Romanticization and commercialization of the aesthetics of scavenging are often at work, taking advantage of the image of green as the new black. Without giving up on its traditional and scandalously wasteful light decorations, highly hypocritically, this year Paris has also scavenged some green plastic bottles to erect an additional four eco-chic Christmas trees. Holiday resorts that will increase your carbon footprint tenfold are innocently advertised for their ecological credentials. The designer brothers Humberto and Fernando Campana have built their celebrity image and an entire career on an exploitation of the appearance of makeshift constructions, waste reuse and recycling, highjacking radical bricolage 'aesthetics of garbage' (film director Eduardo Coutinho's term)(7) from their social and political context, and turning their primitive-looking, poverty-chic creations into luxury design icons. Their bourgeois eulogy of garbage is not only highly resource wasteful but politically reactionary too, much like Favela Chic nightclubs in Paris and London, serving customers in search of an exotic experience.

Paris, Christmas 2009, photographs by Styliane Philippou

Humberto and Fernando Campana, Favela chair, 1991, manufactured by Edra, Italy,

photograph by Styliane Philippou

Favela Chic, nightclub, Paris, 2004, photograph by Styliane Philippou

No luxury icons, however, could ever outshine the spectacular, cascading, sparkling wall hangings of Ghanaian sculptor El Anatsui. In 2005, his eight-metre long, beautifully shimmering Cloth of Gold, composed of thousands of flattened aluminium bottle screw-caps, was the gorgeous centrepiece of the exhibition Africa Remix: Contemporary Art of a Continent (10 February - 17 April) at the Hayward Gallery, London. During the 2007 Venice art biennale, as part of the exhibition Artempo: Where Time Becomes Art, his sumptuous textile installation Fresh and Fading Memories dressed the façade of the Gothic Palazzo Fortuny, former home and atelier of Spanish couturier Mariano Fortuny. The glimmering swatches of the immense metal tapestry, with their brand names visible, uplifting and historically grounded, alluded to both the city's old mercantile splendour and the economics of the shameful transatlantic slave trade, in which alcoholic spirits played a key role as the chief exchange commodity. In Venice, El Anatsui's radical transformation of detritus and industrial leftovers produced an emblematic symbol of the power of wealth.

El Anatsui, Cloth of Gold, 2005, Hayward Gallery, London, photographs by Styliane Philippou

Artists, from Marcel Duchamp to Jean Tinguely and Jannis Kounellis, have frequently used mundane or discarded objects to dignify the commonplace, reassemble and transform the undistinguished and the salvaged junk into a new work of art. Romuald Hazoumé, from the Republic of Benin, creates highly evocative sculptures made of found objects, primarily petrol canisters, criticizing post-colonial African economic dependencies, drawing attention to social injustice and illegal practices in contemporary Benin life, and questioning western preconceptions of African art. His poignant sculpture Liberté, inspired by a Western 'mask', reverses a process that began one century earlier, when European artists like Pablo Picasso 'discovered' and found inspiration in the art of Africa, remapping colonialist perceptions of cultural exchanges between Africa and the Western world, and challenging traditional views about currents in the world of art, which tend to assume that these flow unidirectionally, from the hegemonic core countries to those on the periphery of power.

Romuald Hazoumé, Liberté, 2009

Hazoumé won the prestigious Arnold Bode prize at Documenta 12, in 2007, Kassel, Germany, with his work entitled Dream, a long boat constructed of 421 black oil cans and installed in front of a photograph of an idyllic beach where children crowd 'damned if they leave and damned if they stay: better, at least, to have gone, and be doomed in the boat of their dreams'. Each petrol container resembles a mask, a passenger of one of the thousands of ships that transported slaves to the Americas, and continue to transport those who continue to flee their countries in search of a supposedly better life, a vessel of hope and often of death.

Jackie Wullschlager, art critic of the Financial Times, entitled her review of Documenta 12 'We Know Our Time Is Up', praising the curators for an 'enlightening, thrilling art show [that was] genuinely of the world, rather than a Euro-American take on global culture'.(8) Whether art or life is concerned - and, unless we reduce humans to their animal condition or ignore art's relevance to the material realm of human life, we could not possibly discuss the two separately - our time is up; business as usual is not an option in our fragile material world. In the aftermath of Copenhagen, the politics of artists and communities actively engaged in creative scavenging and urban hunter-gathering seems to go further than the politics of governments; their projects express with a sense of urgency the need and the possibility to transform strategies of survival into a poetics of survival, and to distinguish between the long-term ιinterests of the planet from short-term corporate vested interests.

Notes

1 Quoted in Slessor, Catherine, 2009, 'Eco Activist Wangari Maathai Keeps Her Faith in the Power of Grassroots', Architectural Review, p. 18.

2 According to a recent report of the Energy Commission of the Technical Chambers of Greece, as far as the development of wind-power projects is concerned, 'Greece is the only country that moves backwards instead of moving forwards'. «Αιολική Ενέργεια: Εφαρμογές και Προβλήματα της Διείσδυσης Μεγάλης Κλίμακας» (Chalkida, 10-11 April 2009), library.tee.gr/digital/m2383/m2383_me_energias.pdf

3 Brian Davey, 2009, 'After Copenhagen', 21 December, http://opendemocracy.org/brian-davey/after-copenhagen.

4 http://www.fao.org/newsroom/en/news/2006/1000448/index.html

5 http://sanjeevshankar.com/jugaad.html

6 See Loomis, John A., 1999, Revolution of Forms: Cuba's Forgotten Art Schools (New York: Princeton Architectural Press).

7 Quoted in Stam, Robert, 1997, Tropical Multiculturalism: A Comparative History of Race in Brazilian Cinema and Culture (Duke University Press: Durham and London), p. 56.

8 Wullschlager, Jackie, 2007, 'We Know Our Time Is Up', Financial Times, 15 June.

Related articles:

- 360 Degrees Architecture ( 10 October, 2009 )

- Τhe Roots of the Industry of the Image ( 27 October, 2009 )

- Anish Kapoor: Non-objective Objects ( 26 November, 2009 )

- Europe’s Civilization under Threat ( 28 January, 2010 )

- Made of Stone and Water, for the Human Body ( 28 February, 2010 )

- Bokja: ‘A Woman’s Affair’ ( 28 March, 2010 )

- Brasília from the Beginning, Fifty Years Ago ( 07 April, 2010 )

- Brasília, ‘capital of the highways and skyways’ ( 30 April, 2010 )

- Oscar Niemeyer’s Permanent International Fair in Tripoli ( 29 May, 2010 )

- Learning from Miami ( 10 July, 2010 )

- The Greatest Show on the Beach ( 08 August, 2010 )

- Oscar Niemeyer: Curves of Irreverence ( 28 March, 2011 )

- The Lizards of Djenné ( 26 September, 2010 )

- Transformed by Couture ( 29 October, 2010 )

- Another Athens Is Possible ( 02 December, 2010 )

- From Juan O’Gorman for Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo ( 28 February, 2011 )

- Roberto Burle Marx: The Marvellous Art of Landscape Design ( 27 May, 2011 )

- The Danger that Lurks on this Side of the Gates ( 10 September, 2011 )

- Eduardo Souto de Moura ( 21 November, 2011 )