COLUMNS

360º Architecture

21 November, 2011

Eduardo Souto de Moura

A Tale of Two Chimneys and Other Stories

This year's Pritzker Architecture Prize was awarded to Eduardo Souto de Moura (1952-), the second Portuguese architect to receive architecture's most prestigious honour in less than a decade. His oeuvre, like that of Álvaro Siza Vieira - the 1992 Pritzker laureate - is characterized by a distinct dexterity in the use of craftsmanship and a resourcefully employed reduced palette of materials, which, combined with an ability to reinterpret traditional forms of monumentality with a deft sense for mischief, succeed in turning limited resources and 'technological scarcity' into powerful creative forces. Another Portuguese architect and writer, Pedro Gadanho, has singled out 'the idea of scarcity...as a conceptual driving force for a long-established way of producing architecture' in Portugal. Although not referring to Souto de Moura in particular, already in 2006 Gadanho argued that 'inventive practice' and 'concern for sustainable and critical resourcefulness' may be the appropriate strategies to 'deal with the economical and social crisis that recently hit [Portugal]...a country now divided between its European and Southern identity'.(1) The international recognition of Souto de Moura's work, in the midst of today's global economic crisis, calls attention precisely to these qualities of his work.

Souto de Moura and his fellow Oporto-based architect and former employer, Álvaro Siza Vieira, have collaborated on a number of projects, including the competition entry for the Museum of Cotemporary Art in Helsinki (1992, unrealized), the Portuguese Pavilions for Expo '98 in Lisbon and Expo 2000 in Hanover (rebuilt in Coimbra), and the Serpentine Gallery Summer Pavilion of 2005 in London's Hyde Park (with structural engineer Cecil Balmond). The latter, together with this year's Serpentine Gallery Summer Pavilion by Peter Zumthor - the 2009 Pritzker laureate - are the two least iconic of all Serpentine Gallery Summer Pavilions since 2001, and, thus, also the two least appealing to the kind of media consumption that feeds on the instantly recognizable products of popular architectural celebrities.

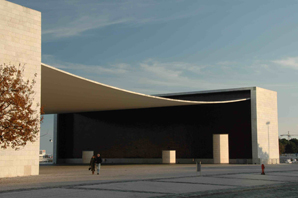

Álvaro Siza Vieira and Eduardo Souto de Moura, Portuguese Pavilion for Expo '98, Lisbon, top and bottom left; Álvaro Siza Vieira and Eduardo Souto de Moura, Portuguese Pavilion for Expo 2000, Hanover, bottom right. Photographs by Styliane Philippou

Álvaro Siza Vieira and Eduardo Souto de Moura, Serpentine Gallery Summer Pavilion 2005, Hyde Park, London. Photographs by Styliane Philippou

Peter Zumthor, Serpentine Gallery Summer Pavilion 2011, Hyde Park, London. Photographs by Styliane Philippou

In his presenting speech at the Pritzker Prize ceremony at the White House, US President Barack Obama suggested that 'architecture can be considered the most democratic of art forms', and praised Souto de Moura for having 'spent his life not only pushing the boundaries of his art, but doing so in a way that serves the public good'. Obama noted a combination of 'artistry and accessibility' in Souto de Moura's work, and singled out the architect's 30,000-seat Municipal Football Stadium in Braga (1999-2003), built for the 2004 European championship in Portugal, as a special example of a democratic building. Souto de Moura, Obama explained, 'took great care to position' the Braga Stadium on the side of a mountain 'in such a way that anyone who couldn't afford a ticket could watch the match from the surrounding hillsides'.

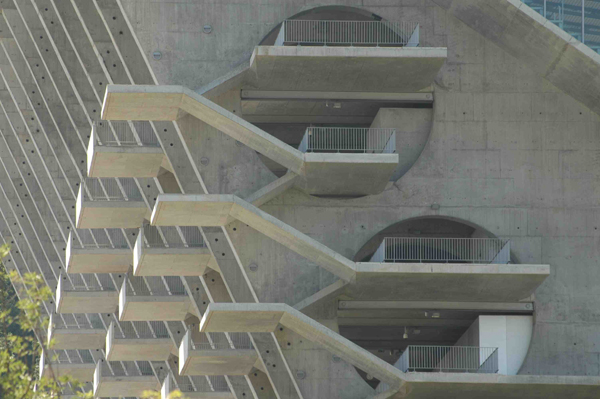

Portugal's northernmost new stadium for Euro 2004 was also its undeniable architectural star, designed by an architect who has successfully protected himself from the pitfalls of architectural stardom. A radical reinvention of the modern football stadium with echoes of ancient Greek and Roman amphitheatres, the sports venue at the historic city of Braga was ingeniously integrated into the surrounding landscape. Rather than a found landscape, however, the latter is itself the result of Souto de Moura's powerful architectural intervention. The two imposing grandstands of the stadium appear to emerge from the thirty-metre-high block of uncut stone, in the manner of a Rodin sculpture, inspired, in turn, by Michelangelo's unfinished slaves. The aggregate used to make the concrete for the sculptural two-tiered stands - one million cubic metres of granite - was, in fact, blasted out of the hillside. Through an operation of monumental proportions, which involved a series of precise explosions and the anchoring of steel reinforcement bars to the rock, to prevent landslides, Souto de Moura sought to harness the forces and energies that mould the surface of the earth, to shape a mighty stone amphitheatre and insert the sporting spectacle in its raw embrace. The south-west stand represents a modern instance of rock-cut architecture, while the north-east stand juts out to the public area of the park, turning the circulating spectators themselves into spectacle.

Eduardo Souto de Moura, Municipal Football Stadium, Braga, 1999-2003. Photograph by Styliane Philippou

The missing limbs of Souto de Moura's monumental sculpture for Braga are the football stadium's typical curvas, the cheaper seating areas behind the goals, traditionally occupied by the more riotous fans. In The Architectural Review, Catherine Slessor characterized the gesture as 'perhaps an over-optimistic speculation on the social decline of tribalism'. Acknowledging the successful optimization of viewing conditions, she added that Souto de Moura 'regards [his solution] as a simple expedient that reflects both football's evolving culture and the increasingly exacting demands of the paying public.'(2) With this mischievous mutilation of the stadium's tribal curvas, Souto de Moura may have also wanted to assert the pleasure in viewing the spectacle of 'the beautiful game' at the real, physical space of the stadium, at a time when sporting events, for most viewers, take place in the virtual and mediated space of television. Ironically, Souto de Moura's amphitheatre itself was confirmed as subject of mediated cultural consumption less than a year after its inauguration, when it was granted national heritage status.(3)

Eduardo Souto de Moura, Municipal Football Stadium, Braga, 1999-2003. Photograph by Styliane Philippou

Eduardo Souto de Moura, Municipal Football Stadium, Braga, 1999-2003. Photograph by Styliane Philippou

It was Souto de Moura's latest and perhaps his most iconic project that drastically increased the public visibility of his architecture. Completed in 2009 and also among the projects cited by Pritzker jurors, the Casa das Histórias Paula Rego at Cascais, near Lisbon, is a small museum dedicated to Portugal's most famous living artist, Britain's Dame Paula Rego (1935-). It was conceived by Cascais mayor António d'Orey Capucho as one of a series of small projects intended to create a 'contemporary architectural heritage', over a period of twelve years, to attract more tourists to the coastal town. One of the first of these projects was the Santa Marta Lighthouse Museum, opened in 2007, designed by Francisco and Manuel Aires Mateus. Celebrating the seafaring nation's pre-eminent building of industrial heritage and Cascais landmark, it comprises three pre-existing white-tile-clad buildings, set around the still-operational nineteenth-century lighthouse, and a new white-rendered volume, accommodating ancillary facilities.

Francisco and Manuel Aires Mateus, Santa Marta Lighthouse Museum, Cascais, 2007. Photograph by Styliane Philippou

Eduardo Souto de Moura, Casa das Histórias Paula Rego, Cascais, 2005-09. Photograph by Styliane Philippou

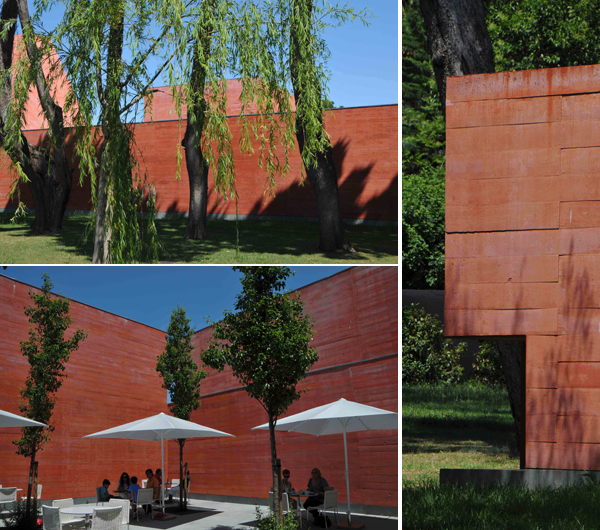

Somewhat paradoxically, the defining feature of Souto de Moura's scarlet, exposed-concrete building - two soaring truncated pyramids along the entrance axis - grants it a scale and character at once monumental and domestic, commensurate with the scale and character of Rego's weird wonderland stories, whose imagery derives from Portuguese women's oral tradition and figurative azulejos, from comic books, William Hogarth's prints and Disney films, from religious iconography, Catholic ex-votos, English nursery rhymes and literature, and from the artist's own childhood memories, dreams and fears, private experiences and myth-making imagination. Souto de Moura's sources of inspiration for his House of Stories range from Claude-Nicolas Ledoux and Aldo Rossi to the early-twentieth-century Casas Portuguesas of Raul Lino (1878-1974), the architect credited with leading 'the nationalization of Portuguese architecture'.(4) Of the museum's two large pyramids, Souto de Moura simply says that they 'prevent the project from being a neutral sum of boxes'. But, like so many of Rego's figurative pictures, the monumental, chimney-like, twin volumes of the House of Stories also retell an old Portuguese tale.

One of Portugal's most celebrated historic monuments, the National Palace of Sintra or Paço da Vila (Town Palace) is located only 11km from Cascais. Two gigantic, conical chimneys dating from the reign of Dom João I (1357-1433) dominate this mediaeval royal residence, and have become the definitive landmark of the coastal town of Sintra, one of Portugal's most visited. The originality of these emblematic, thirty-three-metre-high kitchen chimneys lies not merely in their extraordinary size and grandeur, but, more significantly, in their drawing attention to the domestic character of the royal household, as opposed to its representational function, and in their conspicuous fêting of the noble building's kitchen, a strictly utilitarian space traditionally condemned out of sight, delegated to invisible or painstakingly disguised service quarters. Evoking the scale and vocabulary of industrial architecture, Sintra's stark, undecorated chimney shafts grant the Portuguese monarchs' favourite summer palace a peculiarly modern resonance. Their straightforward form-follows-function bodies overshadow the richly ornamented, low-lying structures of the historic complex, unexpectedly inverting established hierarchies. Acknowledging the historic significance of Sintra's monumental kitchen chimneys, in 1899 Raul Lino quoted them in his competition entry for the Portuguese Pavilion at the Paris Exposition Universelle of 1900 (won by Miguel Ventura Terra). Lino was also responsible for restoration work at the palace in the 1940s.

National Palace of Sintra or Paço da Vila (Town Palace), Sintra, 15th-18th c., photograph by Styliane Philippou, left; Raul Lino, proposal for the Portuguese Pavilion at the Paris Exposition Universelle of 1900, drawing detail, 1899 (unrealized), right.

The story of the heroic chimneys of Sintra, near the popular seaside town of Estoril, where Paula Rego grew up, assumed a central position in Souto de Moura's House for the London-based Portuguese story-teller, whose skewed narratives and twisted family dramas focus on the domestic hearth, 'the real theatre of the sex war', in Germaine Greer's words. After visiting Rego's 1988 retrospective exhibition at the Centro de Arte Moderna in Oporto, the author of The Female Eunuch, whom Paula Rego chose to paint in 1995, when London's National Portrait Gallery commissioned her to do a portrait, wrote: 'Paula Rego is a painter of astonishing power, and that power is undeniably, obviously triumphantly female. Her work is the first evidence I have seen that something fundamental in our culture has changed: the carapace has cracked and something living, hot and heavy, is welling through.' And more recently Greer affirmed: 'No other artist has ever come close to capturing Rego's sense of the phantasmagoria that is female reality'.(5) It is fitting that the large kitchen fireplaces emerge triumphant above the House of Stories inherited and reinvented by Paula Rego, where she delights in 'turn[ing] the tables and...mak[ing] women stronger than men'. Her favourite themes, she wrote already in 1985, are 'power games and hierarchies'; her women are in control of vulnerable men, cruel and tender, 'obedient and murderous at the same time'.(6) And nothing is as it seems.

Eduardo Souto de Moura, Casa das Histórias Paula Rego, Cascais, 2005-09. Photographs by Styliane Philippou

Eduardo Souto de Moura, Casa das Histórias Paula Rego, Cascais, 2005-09. Right, interior of pyramid with skylight. Photographs by Styliane Philippou

Down Souto de Moura's turret holes there are none of Rego's paintings, collages drawings or prints. The chimney-like monumental towers do not mark the museum's most important spaces. And critics mistook them for historicist formalism. Rather than rising above exhibition galleries, as might have been expected of them, the twin turrets are inhabited by a kitchen-restaurant, the domestic hearth Rego identifies with women, children and servants - her disregarded, unsung heroes whose stories she tells - and where the action in her pictures almost always takes place, and a bookshop, her treasure trove of stories. Reversing expectations, that is, the architect Rego herself selected to design the museum dedicated to her work chose to privilege and celebrate precisely those spaces which are at the heart of Rego's imagination. His mischievous gesture is the truest expression of his loyalty to the artist who favours such constant surprises and reversals in her own work, 'supremely uninterested in conforming to what might be expected of her or of her characters'.(7) Perhaps in Souto de Moura's mind was also Rego's seminal pastel series Dog Women (1994), inspired by an old grisly Portuguese tale of an old lady who eats her pets one by one, commanded by the voice she heard of a wailing child as the wind swept down a chimney. Working closely with Rego, who delights in the tactile qualities of materials like her favourite pastels, Souto de Moura also chose in-situ-cast concrete, carefully designing the shuttering so as to produce the desired texture-rich surfaces, again opting for a special herringbone pattern to animate the sloping walls of the chimneys. The concrete walls sit on a low plinth clad in mármore azulino, the blue-grey marble of Cascais he also used to pave the path that leads to the entrance and the museum's floor.

Eduardo Souto de Moura, Casa das Histórias Paula Rego, Cascais, 2005-09. Photograph by Styliane Philippou

Eduardo Souto de Moura, Casa das Histórias Paula Rego, Cascais, 2005-09, detail of exposed-concrete wall surface. Photograph by Styliane Philippou

Raul Lino, Casa dos Penedos, Sintra, 1922. Photograph by Styliane Philippou

'After the painter Paulo Rego chose me as her architect', explains Souto de Moura, 'I was lucky to be able to choose the site. It was a fenced off forest with some open space in the middle. On the basis of the elevation of the trees, I proposed a set of volumes of varying heights. Developing this play between the artificial and nature helped define the exterior color, red concrete, a color in opposition to the green forest'.(8) An earthen-red rendering is not unusual in this region, and Souto de Moura cites Raul Lino's Casa dos Penedos in Sintra (1922). But he also remembers an episode that occurred in 2004, when he visited Rego's exhibition at Tate Britain, upon her invitation. She took him to a room where Francis Bacon's orange-backdrop pictures hung against dark purple walls and exclaimed: 'Look, this is what turns me on!'(9) She had already painted Germaine Greer in her favourite bright red Jean Muir dress. And for the series of Eamonn McCabe's recent photographic portraits of Rego, she donned a dark crimson velvet dress and posed in front of a painting showing Lila Nunes - her favourite model since 1988 - wearing the same red dress. The luxuriously textured, fiery-red house made to measure for her fabulous stories must have pleased her enormously. She had asked Souto de Moura to create a place for 'stories and drawings', which she wished to be 'fun, unpretentious, lively, full of joy and with lots of mischief'.(10) And he designed a domestic-size, bright-red palace with two defiant, seventeen-metre-high chimneys that retell an old Portuguese tale.

'I like to play', Rego keeps repeating, 'although the games can go very dark', and dark is often a label critics attach to her marvelous story-telling pictures. She has a keen eye for what she calls 'the beautiful grotesque' or 'the grotesque beautiful', and a sure way to turn the sinister and terrifying seductive. 'You know what they call it?' she asked The Guardian's Simon Hattenstone on their visit at Cascais, giggling. 'The crematorium.'(11) Apparently, the Casa das Histórias Paula Rego was the talk of the town before its inauguration. Rego may be pleased there is a dark side, perhaps a secret or a sense of menace about the Casa das Histórias, like in all domestic scenes depicted in her pictures. As the Portuguese grande dame says, the 'old Portuguese folktales' that she desperately wants to 'keep alive...they are what gives energy to the country...they are grotesque, of course, and they are full of violence, but they are also love. They are very extreme...they speak a language which is Portugal'.(12) As for the tale of two chimneys, 'there is no end to a story, it unfolds all the time'.(13)

Eduardo Souto de Moura, Casa das Histórias Paula Rego, Cascais, 2005-09. Photograph by Styliane Philippou

Notes

1 Gadanho, Pedro, 2009, 'Will the South Rise Again? (On the Emergency of Emergency)', 2GDossier Iberoamérica: Emerging Architecture (Barcelona: GG), pp. 114-16.

2 Slessor, Catherine, 2004, 'Sports Spectacle', The Architectural Review 216, no. 1289 (July), p. 44.

3 Gadanho, Pedro, 2007, 'This Is Portugal...', http://shrapnelcontemporary.wordpress.com/2009/01/19/this-is-portugal/

4 See Milheiro, Ana Vaz, 2009, 'O Arquitectar das Casas Simples'. In Casa das Histórias Paula Rego (Cascais: Casa das Histórias Paula Rego), pp. 17-35; quotation on p. 27.

5 Greer, Germaine, 2004, 'Untamed by Age', The Guardian, 20 November, http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/2004/nov/20/art

6 Quoted in Jaggi, Maya, 2004, 'Secret Histories', The Guardian, 17 July, http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/2004/jul/17/art.art

7 Fiona Bradley quoted in Mackenzie, Suzie, 2002, 'Don't flinch, don't hide', The Guardian, 30 November, http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/2002/nov/30/art.artsfeatures

8 Quoted in the Announcement of the Pritzker Architecture Prize, http://www.pritzkerprize.com/laureates/2011/announcement.html

9 Grande, Nuno, 'O Palácio Escarlate'. In Casa das Histórias Paula Rego (Cascais: Casa das Histórias Paula Rego), p. 14.

10 Quoted in Grande, p. 15.

11 Hattenstone, Simon, 2009, '"You punish people with drawing"', The Guardian, 22 August, http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/2009/aug/22/paula-rego-art-interview

12 Paula Rego interviewed by Carrie Gracie, The Interview, BBC World Service, 9 October 2010, http://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/episode/p00b40x3/The_Interview_09_10_2010_Paula_Rego/

13 Paula Rego quoted in Mackenzie, Suzie, 2002, 'Don't flinch, don't hide', The Guardian, 30 November, http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/2002/nov/30/art.artsfeatures

Related articles:

- 360 Degrees Architecture ( 10 October, 2009 )

- Τhe Roots of the Industry of the Image ( 27 October, 2009 )

- Anish Kapoor: Non-objective Objects ( 26 November, 2009 )

- Love Thy Planet ( 28 December, 2009 )

- Europe’s Civilization under Threat ( 28 January, 2010 )

- Made of Stone and Water, for the Human Body ( 28 February, 2010 )

- Bokja: ‘A Woman’s Affair’ ( 28 March, 2010 )

- Brasília from the Beginning, Fifty Years Ago ( 07 April, 2010 )

- Brasília, ‘capital of the highways and skyways’ ( 30 April, 2010 )

- Oscar Niemeyer’s Permanent International Fair in Tripoli ( 29 May, 2010 )

- Learning from Miami ( 10 July, 2010 )

- The Greatest Show on the Beach ( 08 August, 2010 )

- Oscar Niemeyer: Curves of Irreverence ( 28 March, 2011 )

- The Lizards of Djenné ( 26 September, 2010 )

- Transformed by Couture ( 29 October, 2010 )

- Another Athens Is Possible ( 02 December, 2010 )

- From Juan O’Gorman for Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo ( 28 February, 2011 )

- Roberto Burle Marx: The Marvellous Art of Landscape Design ( 27 May, 2011 )

- The Danger that Lurks on this Side of the Gates ( 10 September, 2011 )