COLUMNS

360º Architecture

27 October, 2009

Τhe Roots of the Industry of the Image

While researching the history of an unusual Parisian apartment, behind a rather ordinary mid-nineteenth-century façade, a most amazing story was unveiled to me. It involves art, photography, the publishing industry and architecture.

Overlooking the typical Parisian courtyard of the neoclassical building at 9 rue Chaptal, in an area of the 9th arrondissement developed in the 1820s and known as Nouvelle Athènes, is the space originally conceived as an art gallery for the Maison Goupil, the leading fine art dealer and publisher in nineteenth-century France, and first international art publisher. Jean Baptiste Michel Adolphe Goupil and his wife Victorine Elisabeth Brincard bought the land at 9 rue Chaptal in 1857, and constructed the Hôtel Goupil, headquarters of Goupil & Cie from 1860 to 1893. The home of the Goupils was on the first floor of the building, which also housed a shop selling original artworks along with reproductions, printing workshops, as well as apartments let to artists holding exclusive contracts with the company for the reproduction of their works. The Goupils' annual costume ball was a highly expected event among Parisian artists. (1) The Goupil gallery, a rather more exclusive venue in comparison with the company's three Parisian salerooms, was a steadfast champion of the academic French art of the period, legitimized by the juried Salon of the Académie des Beaux-Arts at the Louvre, the undisputed showcase of French art. From 1878, however, Theo van Gogh, brother of the painter, became instrumental in the company's promotion of the refusés of the official Salon de Paris.

Hôtel Goupil, 9 rue Chaptal, Nouvelle Athènes, Paris, photograph by Styliane Philippou

The art gallery of the Maison Goupil overlooks the courtyard of the Hôtel Goupil.

Photograph by Styliane Philippou

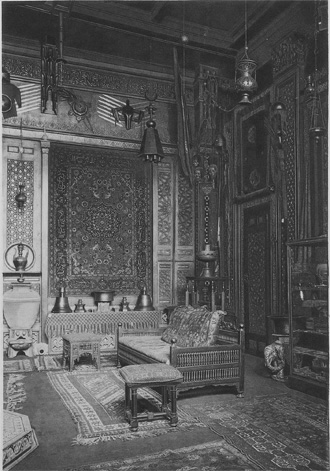

In 1884, the 'renowned atelier' created at 9 rue Chaptal by the photographer Albert Goupil, son and associate of Adolphe, was celebrated as 'one of Paris's marvels', for its extraordinary assembly of precious furniture, historic costumes, Persian carpets, Arabic glassware, fifteenth-century tapestries etc, and exceptional artworks including a 'superb collection of paintings by Ingres'. Émile Molinier, of the Louvre's department of conservation of mediaeval and Renaissance monuments, dedicated a long article to Albert Goupil's eclectic taste. He described two salons at the Hôtel Goupil, 'one dedicated to the East and the other to the Renaissance, [which] allow[ed] their owner to move between a palace of A Thousand and One Nights and the residence of a grand seigneur of the sixteenth century, always amidst first-class artworks'.(2) Following the early death of Albert Goupil, the greatest of these treasures such as a bust by Donatello were offered to France's national collections. Albert Goupil's Orientalist salon was indeed as flamboyant as the scenery in the works of Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824-1904), one of France's greatest academic masters, close friend and son-in-law of Adolphe Goupil. Fascinated by the colours of the East, the two men, together with another two French painters (Léon Bonnat and Ernest Journault), two of Gérôme's students (Paul-Marie Lenoir and Jean-Richard Goubie) and a Dutch Orientalist painter (Willem de Famars Testas), travelled over four months in 1868, from Egypt to Petra and Jerusalem. Albert Goupil's photographs served the painters of the expedition by providing them with an exact record of places and scenes that would later appear in their paintings, produced in their European ateliers with the help of their own sketches and the photographer's prints. (3)

The 'Oriental' salon of Albert Goupil, 9 rue Chaptal, Paris, prior to 1888, Catalogue des objets d'art de l'Orient et de l'Occident, tableaux, dessins composant la collection de feu M. Albert Goupil, Paris: Drouot, Mes Escribe and Paul Chevalier, Charles Mannheim exhibition, Imprimerie de l'art, 23-27 April 1888. Published in Rémi Labrusse, 'Islamophobia? Europe in Conquest of the Arts of Islam', Arts & Societies, http://www.artsetsocietes.org/a/a-labrusse.html

The Maison Goupil was first established in Paris at 12 boulevard Montmartre, by Adolphe Goupil (1806-93), a descendent of the eighteenth-century portraitist François-Hubert Drouais, in partnership with Henry Rittner (1802-40), from Stuttgart, Goupil's future brother-in-law. Rittner's experience in the London print trade and his family of print sellers in Dresden facilitated the company's expansion on a European scale. Rittner & Goupil commissioned the best lithographers and copperplate engravers of the time and produced interpretations of Old Masters (Titian, Raphael, Michelangelo, Veronese etc), but primarily reproductions of works by contemporary artists of the Salon (Delaroche, Ingres, Deveria, Winterhalter etc). Over almost a century (1827-1921), the Maison Goupil - Rittner & Goupil and its successors - exploited traditional and cutting-edge printmaking and photographic technologies, some developed in-house, to meet a growing popular demand for inexpensive art reproductions, producing images in ever greater numbers and at increasingly lower cost, and thus bringing art publishing into the industrial age. In partnership with Théodore Vibert and Alfred Mainguet, in the 1840s, Goupil built a vertically-integrated business with their own printing facilities. The mixed-use Hôtel Goupil would later give spatial expression to this integrated, family enterprise. In 1841, they opened a branch in London, and in 1846 one in New York. Later, there were also branches in The Hague, Berlin, Brussels and Vienna, and sale points in Alexandria, Dresden, Geneva, Zurich, Athens, Barcelona, Copenhagen, Florence, Havana, Melbourne, Sydney, Warsaw, Johannesburg etc. The company was at the centre of an international network of a new generation of art dealers and publishers with unprecedented distribution capacity, which guaranteed significant rewards.

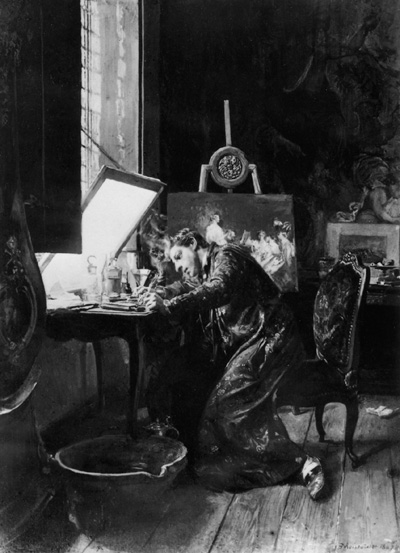

E. Meissonier, Graveur, photographic reproduction by R. J. Bingham, 24 x 14,7 cm, published by Robert Jefferson Bingham, 1 May 1863, French National Library collection

Goupil was the first true industrialist of the image; this is where his historical importance really lies. The advent of photography, in 1839, revolutionized an industry that until then depended on costly and time-consuming processes. At a time when the publisher's conceptualization, organization and printing was routinely prized over the photographers' work, Rittner & Goupil broke new ground with their co-publication of the multi-volume Excursions Daguerriennes : vues et monuments les plus remarquables du globe (1840-44), with more than a hundred travel subjects from Europe and the Near East, followed by major photographic publications over the next decades. The initial emphasis on landscape and architecture soon gave way to fine-art photographic reproductions, including those in the catalogues of the Salons, published by Goupil, a specialization that allowed them to capitalize on their experience as art-print publishers.

Paul Delaroche (1797-1856) was the first artist to have his work reproduced by means of photography. Published by Goupil in 1858, following the large retrospective posthumous exhibition at the École des beaux-arts, L'Œuvre de Paul Delaroche constitutes the first artist's catalogue raisonné to be illustrated with photographs, by the English photographer Robert Jefferson Bingham (1825-1870). A second monograph, in 1860, was dedicated to the Dutch-born French academic painter Ary Scheffer (1795-1858), whose home at 16 rue Chaptal today houses the Musée de la vie romantique. Even though these mid-nineteenth-century monographs were of limited commercial success, because of their high cost, they launched a new kind of art history book, which would eventually become the dominant type of publication in the field. (4)

In 1860, Goupil & Cie opened an in-house photographic studio, in 1867 they bought from Walter Woodbury an exclusive licence for the exploitation of the Woodburytype process in France, and in 1869 they opened a large modern factory in Asnières, driven by steam and, from 1874, by electricity, gathering under one roof all technical and manufacturing activities. The first photogravures were produced in 1873. US publishers often commissioned photogravure printing from Goupil, for the unprecedentedly high levels of quality and accuracy achieved through a process they called 'Goupilgravure'. By 1880, the Asnières factory of what had become the most powerful art publishing company of the nineteenth century employed 107 persons, eighty-five men, thirteen women and nine children. Phototypogravure, also invented by the Maison Goupil, allowed simultaneous printing of photographs and text, thus enabling publication of photographically illustrated books and magazines. (5) Goupil brought about a real revolution in the art of illustration; the pioneer's art publications became increasingly luxurious. In 1897, they printed 125 copies of Les dessins de Auguste Rodin, and in 1900 the New York Times announced the sale of 'another expensive art book from Goupil's...a new and magnificent book on the art and personality of Sandro Botticelli' with about fifty illustrations and in two versions: an 'ordinary edition' at 100 USD and a special one at 200 USD. (6)

L'Établissement photographique de MM. Goupil et Cie, à Asnières, wood engraving by H. Dutheil, published in L'Illustration, no. 1572, 12 April 1873, p. 253

From 1846, the Maison Goupil had also expanded into dealing in drawings and paintings. Initially, this meant selling the drawings commissioned from engravers for the purpose of creating a print from an artwork. Later, Goupil moved on to buying original artworks expressly for the purpose of acquiring copyrights, produced all kinds of reductions and reproductions - from lavish engravings made with a burin to carte-de-visite-sized photographs and even statuettes from subjects in the popular paintings - and finally sold the original work, the reproductions, and permissions for further reproductions such as magic-lantern shows and tapestries, at substantial profit, shared with the artists. The two activities remained closely linked: most of the paintings listed in the first book of the gallery at 9 rue Chaptal (1846-1861) appear also in the company's catalogue of published prints (Brochart, Delaroche, Alfred de Dreux, Guérard, Holfeld, Karl Muller, Ary Scheffer, Schopin, Horace Vernet, Winterhalpter).

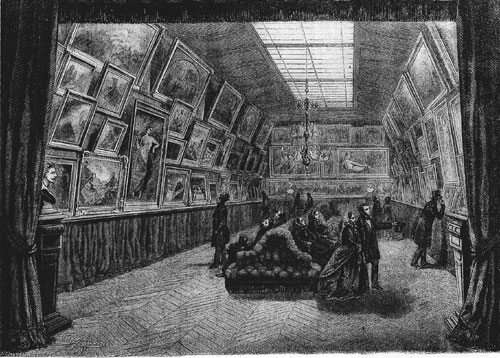

In May 1860, 'hardly one year after the completion of the Hôtel Goupil,' the first exhibition at the new gallery attracted considerable attention in the press: 'upon the request of a great number of painters who regretted not having been able to show their latest work to the public, the Exposition des Beaux-Arts [the Salon] not having taken place this year...the illustrious publishers mounted an exhibition for amateurs, totally free, attended by personal invitation only. At least one hundred canvasses were exhibited, among which the latest works of Achenbach, Boulanger, Brascassat, Cabanel, Cermak, Comte, Curzon, de Dreux, Dubuffe, Gérôme, Gleyre, Knaus, Muller, Petter Koffen, Ph. Rousseau, Toulmouche, Yvon, Jadin etc.' (7) An extensive report in the Gazette des Beaux-Arts described the gallery at 9 rue Chaptal as 'elegant, decorated and furnished with taste, where paintings are displayed in a very favourable light'. It was underlined that the 'generous hospitality' of the Maison Goupil was addressed primarily to young artists, who benefited greatly from this private initiative. (8) The exhibition remained open for a month. Goupil's marketing genius was at work, promoting his brand new venue, the work of about fifty painters, and the arrival of his new partner from Holland, Vincent Van Gogh, uncle and god-father of the painter, who would play a vital role in the growth of the business over the following seventeen years.

One of the three Parisian salerooms of Goupil & Cie, Place de l'Opéra, Paris (1859-1920), http://www.culture.gouv.fr/GOUPIL/FILES/GOUPIL_ADOLPHE.html

Galerie de tableaux de la maison Goupil et Compagnie, éditeurs d'estampes, wood engraving

by A. Jourdain after A. Guesdon, published in L'Illustration, no. 889, 10 March 1860, p. 155

In the nineteenth century, the Van Gogh family held a strong position in the flourishing art trade in The Hague. Vincent van Gogh's gallery occupied the first floor of a handsome nineteenth-century building on the fashionable Plaats. In 1858, 'Uncle Cent' sold his lucrative business to Goupil in exchange for a partnership, and moved to Paris. Goupil's art dealing activity received new impetus, eventually becoming the main activity of the house. (9) On 30 July 1869, at the age of sixteen, Vincent van Gogh began his apprenticeship at Goupil & Cie in The Hague, in 1873 he moved to the London branch, and in 1875 to Paris. But his disapproval for the conventional art on which the company thrived grew increasingly stronger, and on 1876 he was dismissed. His younger brother, Theo, joined the company's Brussels branch in 1873, was transferred to Paris in 1878, and on 1 January 1882 became manager of the establishment at 19 boulevard Montmartre, in the heart of Paris's business district. Vincent wrote to his brother in September 1884: 'In most cases G. & Co. lagged behind with the original artists...Goupil & Co. has always been a bit orthodox...[they] will certainly not do anything with my work for years to come.' (10)

Through Theo, van Gogh obtained a number of prints and books that helped him hone his drawing skills, most importantly the Cours de dessin, one of the most influential classical drawing courses specially produced for art students of the prestigious schools of Paris, compiled by Charles Bargue in collaboration with Jean-Léon Gérôme, and published by Goupil & Cie (1868-1873). On several occasions, van Gogh wrote to his brother how grateful he felt towards his former director at Goupil's in The Hague, Herman Gijsbert Tersteeg, for lending him a copy in 1880. The course, which van Gogh copied entirely, was composed of 197 lithographs printed as individual sheets, and intended to guide students from plaster casts to the study of great master drawings, and finally to drawing from the living model. On 24 September 1880, van Gogh commented: 'I am still working on Bargue's Cours de Dessin, and intend to finish it before I go on to anything else, for both my hand and my mind are growing daily more supple and strong as a result.' On 2 April 1881, he begged his brother for more help in his studies of proportion and anatomy, suggesting that he may contact Bargue or Viollet-le-Duc, 'the best source of information'.

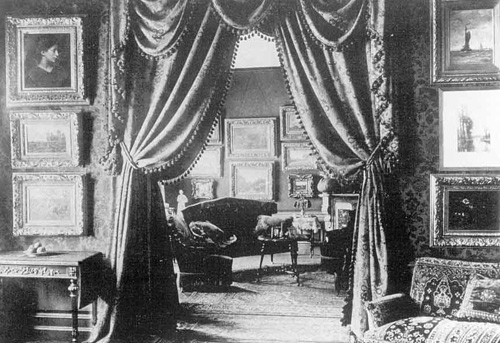

The variety of media, formats and sizes of artworks produced by Goupil changed the experience of viewing art. These reproductions had also a major transformative impact on the nineteenth-century bourgeois home. The Goupil galleries in London and The Hague were set in luxurious domestic interiors stocked with heavy furniture, with which the newly wealthy middle class could identify. The company marketed its products to a global audience, at once creating and satisfying a new market, and advanced a kind of domestic, intimate art for the family drawing room, didactic and decorative. The Maison Goupil's branch in New York promoted the 'goût des Beaux-Arts' in the US, through exhibitions and more intensely through the publication and sale of prints. (11) In 1850, Goupil received an unexpected commercial boost from Andrew Jackson Downing, architect, landscape architect, writer, editor of the Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste, and apostle of taste, who wrote in his highly popular The Architecture of Country Houses:

There are few persons living in cottages who can afford to indulge a taste for pictures. But there are, nevertheless, many in this country who can afford engravings or plaster casts, to decorate at least one room in the house. Nothing gives an air of greater refinement to a cottage than good prints of engravings hung upon its parlor walls. In selecting these, avoid the trashy, colored show-prints of the ordinary kind, and choose engravings or lithographs, after pictures of celebrity by ancient or modern masters. The former please but for a day, but the latter will demand our admiration forever. Messrs. Goupel [sic], Vibert & Co., Broadway, New York, offer the largest collection of fine prints in the country. (12)

The Maison Goupil's Gallery in the Hague, photograph, published in sorrel.humboldt.edu/~rwj1/van/007.html

In the second half of the nineteenth century, Goupil & Cie's commercial activities positioned them at the centre of a new debate over the relations between art and society. Their industrialization of art was both praised for its contribution to the dissemination of art among the widest public, and held responsible for the commercialization and banalization of art. Following the Exposition universelle of 1867, and again in 1878, Émile Zola castigated the Maison Goupil for promoting the production of paintings destined exclusively for mass reproduction as decorative items for 'bourgeois salons'. (13) Their policy, he argued, encouraged a shift of emphasis from painting to its subject matter, so as to produce 'pretty and proper' pictures of all types of content - from the patriotic to the lecherous - in order to please everyone: 'Obviously, Mr Gérôme works for the Maison Goupil; he creates his canvases in order that they may be reproduced by photography and engraving, and sold in thousands of copies...There is hardly a provincial salon without an engraving of [Gérôme's] Duel au sortir d'un bal masqué or Louis XIV et Molière; in boys' quarters we find [La danse de l']Almée and Phryné devant un tribunal, piquant subjects permissible among men. For the austere, there are Les Gladiateurs or La Mort de César.' (14)

The highly profitable collaboration between the astute businessman Goupil and the talented Jean-Léon Gérôme, one of the house's most important artists, was typical of a time when the art-publishing industry boosted dramatically international demand for the art of the Paris Salon, and the fortunes of its favourites. Artworks were mass produced, marketed and distributed widely to a middle class growing bigger and richer, a media explosion that contributed to the rise of the international speculative art market as we know it today. Of 337 sold Gérôme paintings, 122 were made into about 370 print editions, turning the French academician into an international celebrity. Ridley Scott's Gladiator, based on Gérôme's grandiloquent Pollice Verso of 1872, has extended his popularity to the twenty-first century. As with regard to the continuing massive popularity of the fashion launched by the leading industrialists of the image and the artists and architects of the nineteenth century, for decorating the domestic interior (and not only) with art reproductions, there is no doubt that it has gone from strength to strength, aided by the continuous development of printing technologies, and the ever lower prices of its products. Eager to suit the tastes of his clients, Gérôme even proposed the reproduction of his most famous canvases, like Duel au sortir d'un bal masqué (1857, The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg), in multiple versions, to go with the colours of the buyer's apartment. Long before Andy Warhol, the widespread dissemination of Goupil's prints began to blur the boundaries between high art and popular culture.

Many of Goupil's and Gérôme's clients were American. Despite condescending reviews from high-brow critics on both sides of the Atlantic, Gérôme's technical mastery, the archaeological exactitude of his epic evocations of classical antiquity, and the exoticism of his flamboyant orientalist pictures did not fail to seduce American collectors, mostly wealthy businessmen and bankers, who paid increasingly higher prices for his works. The wealthiest families, including the Astors and the Vanderbilts, purchased paintings, while the expanding middle class bought prints. US art dealers referred to the romantic painters favoured by the French company as 'The School of Goupil'.(15) More than two thousand students, including many Americans, learnt their craft at the atelier of Gérôme, Professor at the École Nationale des Beaux-Arts for almost forty years, from 1864 to 1902. One of his last students was Fernand Léger. Gérôme's influence over Goupil's choice of artists should not be underestimated either. All the celebrities of nineteenth-century French art moderne sanctioned by the Salon were reproduced by the Maison Goupil, who received numerous decorations and support from the government for their patronage and international diffusion of French academic art.

Goupil's pursuit of the gratification of bourgeois tastes did not escape Vincent van Gogh's notice: 'Fortunately it is very easy to sell nice polite pictures in a nice polite place to a nice polite gentleman. Now that the great Albert [Goupil] has given us the recipe, every difficulty has disappeared by magic,' he wrote from Arles on 5 June 1888. 'Nothing', he argued the following month (19 July 1888), 'would help us to sell our canvases more than if they could gain general acceptance as decorations for middle-class houses. The way it used to be in Holland'. Yet, since the arrival of Theo van Gogh in Paris, the list of artists registered with Goupil had changed rapidly and radically: Eugène Boudin, Paul Cézanne, Edgar Degas, Édouard Manet, Claude Monet, Paul Gaugin, Camille Pissarro, Alfred Sisley, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. It is at his time with the Maison Goupil that Theo van Gogh owes his reputation as a champion of the Impressionists. Following his departure, however, in 1890, the company's director, Léon Boussod, urged Maurice Joyant: 'our manager, a kind of crazy man, like his brother, has entered an asylum; go to replace him and do as you please. He has accumulated some hideous modern painters who are disgracing the house.' (16)

The Maison Goupil played a major role in the art media explosion of the nineteenth century, and in the industrialization and commodification of the image. But its ultimate successor, Manzi, Joyant & Cie, did not survive World War I and the changes of fashion; they ceased active operation in 1917. In 1921, Vincent Imberti, a print dealer from Bordeaux, acquired the remaining stock and archive, and in 1987 and 1990 Guy and Gabrielle Imberti ceded what remained to the City of Bordeaux, which founded the Musée Goupil.

Notes

1.Lafont-Couturier, Hélène, 2000, 'M. Gérôme travaille pour la maison Goupil'. In Gérôme & Goupil : Art et Entreprise (Paris: Éditions des musées nationaux, Bordeaux: Musée Goupil, Pittsburgh: Frick Art and Historical Centre and New York: Dalesh Museum of Art, exhibition catalogue), p. 28.

2.Émile Molinier, 1884, quoted in Lafont-Couturier, 2000, p. 17.

3.Lafont-Couturier, 2000, p. 17.

4.Boyer, Laure, 2002, 'Robert J. Bingham, photographe du monde de l'art sous le Second Empire', Études photographiques, no. 12, November, http://etudesphotographiques.revues.org/index320.html#text.

5.Renié, Pierre-Lin, 2005, 'Goupil & Cie'. In John Hannavy (ed.), Encyclopedia of Nineteenth-Century Photography (London: Routledge), 2 vols, vol. 1, p. 603.

6.The New York Times, 1906, 24 February.

7.Vaurert, Maxime, 1860, 'Salons d'exposition de tableaux de MM. Goupil', Le Monde Illustré, no. 161, 12 May, p. 320. The Salon de Paris became biannual between 1855 and 1863.

8.Saglio, E., 1860, 'Exposition de tableaux modernes dans la galerie Goupil', Gazette des Beaux-Arts, vol. 7, 1 July, pp. 46-47.

9.Lafont-Couturier, Hélène, 1996, 'La maison Goupil ou la notion d'œuvre originale remise en question', Revue de l'Art, vol. 112, no. 1, p. 68.

10.All quotations from Vincent van Gogh's letters are from http://www.webexhibits.org/vangogh/

11.From the 1848 catalogue of New York's Goupil, Vibert & Co, quoted in McIntosh, DeCourcy E., 2000, 'Goupil et le triomphe américain de Jean-Léon Gérôme'. In Gérôme & Goupil : Art et Entreprise, p. 33.

12.Downing, A. J., 1969, The Architecture of Country Houses (New York: Dover [1850]), p. 372 (the last sentence appears in a footnote).

13.Lafont-Couturier, 2000, p. 29.

14.Quoted in McIntosh, p. 41.

15.Samuel P. Avery, quoted in House, John, 1998, 'Authority Versus Independence: The Position of French Landscape in the 1870s'. In Thomson, Richard (ed.), 1998, Framing France: Essays on the Representation of Landscape in France, 1870-1914 (Manchester: Manchester University Press), p. 21.

16.Maurice Joyant, quoted in Lafont-Couturier, 1996, pp. 68-69.

Related articles:

- 360 Degrees Architecture ( 10 October, 2009 )

- Anish Kapoor: Non-objective Objects ( 26 November, 2009 )

- Love Thy Planet ( 28 December, 2009 )

- Europe’s Civilization under Threat ( 28 January, 2010 )

- Made of Stone and Water, for the Human Body ( 28 February, 2010 )

- Bokja: ‘A Woman’s Affair’ ( 28 March, 2010 )

- Brasília from the Beginning, Fifty Years Ago ( 07 April, 2010 )

- Brasília, ‘capital of the highways and skyways’ ( 30 April, 2010 )

- Oscar Niemeyer’s Permanent International Fair in Tripoli ( 29 May, 2010 )

- Learning from Miami ( 10 July, 2010 )

- The Greatest Show on the Beach ( 08 August, 2010 )

- Oscar Niemeyer: Curves of Irreverence ( 28 March, 2011 )

- The Lizards of Djenné ( 26 September, 2010 )

- Transformed by Couture ( 29 October, 2010 )

- Another Athens Is Possible ( 02 December, 2010 )

- From Juan O’Gorman for Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo ( 28 February, 2011 )

- Roberto Burle Marx: The Marvellous Art of Landscape Design ( 27 May, 2011 )

- The Danger that Lurks on this Side of the Gates ( 10 September, 2011 )

- Eduardo Souto de Moura ( 21 November, 2011 )